A rough-coated, dough-faced, thoughtful ploughman strode through the streets of Scarborough; after falling into a slough, he coughed and hiccoughed.

1st International Collection of Tongue Twisters, #253, © 1996-2018 Mr. Twister.

AH F, OW, AO, AW, OW, AH F, AO F, AH P

This sentence exemplifies the ambiguous pronunciation of the “ough” in the above words, such as by OW or AH F, which is evident to native speakers but a headache for non-native English learners. This type of ambiguity is a heterophone : same spelling, different pronunciation. For anyone studying English it is soon evident that the written symbols (graphemes) don’t always match the spoken sounds (phonemes). This grapheme-phoneme correspondence in the English language is low (turns out it was more phonemic in the past)… What if we can make it perfect?

Problem: take a phoneme (e.g. OW) and assign it a unique grapheme (e.g. ough).

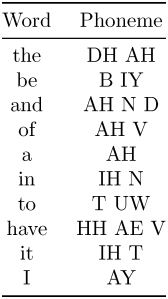

Lets start by getting a dictionary of words and their corresponding phoneme. This data for North American English is available from CMUdict (Carnegie Mellon University Pronouncing Dictionary) which contains over 134,000 words and their pronunciations. Since we do not want to bias the result by archaic or rarely used words (and their corresponding phonemes): only the top 5000 most frequently used words in the English language will be used in the following analysis. Then the top 10 will look like this:

Of course at this point one could just replace all the English alphabetical spelling with the phoneme spelling (e.g. I Have To → Ay Hhaev Tuw) but as you can see it becomes too verbose and alien. The ideal is to reuse the current spelling as compactly as possible.

Simple example: Hello

Lets start simple… with linear algebra. Firstly, by taking a word and mapping it into a vector that spans the “alphabet space”, i.e. each letter of the alphabet is a dimension of the vector, where the value can be 0 or 1 depending on whether or not the corresponding letter is present or not in the word. For example, in Python code, the word “hello” would have the following vector (starting with a and ending with z):

word = [0,0,0,0,1,0,0,1,0,0,0,1,0,0,1,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0]

Note the 26 states of the alphabet space and that despite two instances of the letter “l”, it is only indicated once.

The same approach is then applied to the phonemes in the word. The North American English language has 39 distinct phonemes that can be mapped onto a “Phoneme space” as done above. For example, the phonemes of “hello” are “HH AH L OW” so the vector would look like (starting with AA and ending with ZH):

phon = [0,0,1,0,0,0,1,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,1,0,0,0,1,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0]

The task now is to solve for a transformation matrix that maps vectors from

(phonemes space) to

(alphabet space), which is written as:

. Note that the matrix

will be of size 39 by 26. For this particular case the solution for

is highly under-determined since there is not enough information to solve uniquely for all possible letter-phoneme combinations. Nevertheless, a least-squares (

numpy.linalg.lstsq; see link for details) method can be applied to determine , as shown in the following diagram:

As it turns out the above transformation maps satisfies the relation perfectly. Unfortunately, it resulted in a somewhat nonsensical result implying that the phoneme AH can be represented equally well by any of the letters. Since the values are fractional it can be thought of as implying the likelihood of a letter given the phoneme. Hence, by this interpretation the transformation matrix can be thought of as a correlation matrix (this shift in perspective is necessary to understand negative values).

Analysis with 5000 word data-set

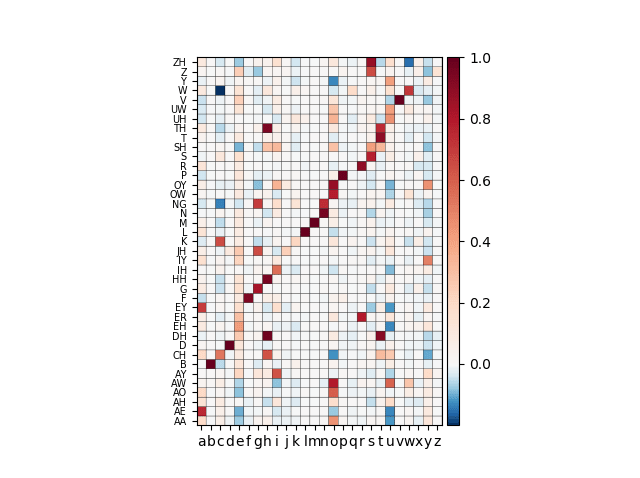

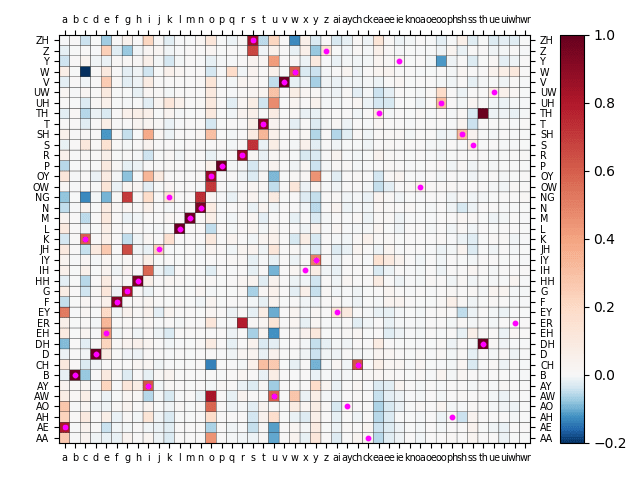

The next logical step is to then take those aforementioned 5000 words and combine them into a large 5000 x 26 size matrix and extract their corresponding phonemes to get a 5000 x 39 size matrix. Since there is considerably more supplied information than before: applying the least-squares solution will generate the transformation matrix that will try to map all the 5000 different word vectors as closely as possible (in the least-squares sense) to the 5000 phoneme vectors. The resulting transformation matrix is shown as follows:

Correlation matrix between the phonemes (vertical axis) and graphemes (horizontal axis). Red is positive correlation; blue is negative correlation. Note the diagonal dark red line pattern indicating a strong correlation between the phonemes and the graphemes along this line.

Now we have something with a clear trend – a dark red line starting from the phoneme B (for the letter b) and ending at W (for w). The dark red color indicates a strong positive correlation between an instance of the phoneme and an instance of the letter. Indeed, the phonemes B, D, F, L, M, P, V, and W are highly correlated with the letters b, d, f, l, m, p, v, w – indicating that this subset is highly phonemic. The contrary case, i.e ambiguous pronunciation, is well exemplified with the letter “o”, which correlates across a wide range of phonemes such as (from high to less correlated) OY, AW, OW, AO, AA, then at about 0.3 level UH, UW, SH. Interestingly, there are blue-colored squares that indicate negative correlation. This means that the presence of the phoneme usually means the given letter is absent in the word. The W phoneme has the largest anti-correlation (-0.2) with the letter “c”. Thinking of an example: we say work not “worck” but we also say flock not “flok”. This example supports the observed anti-correlation.

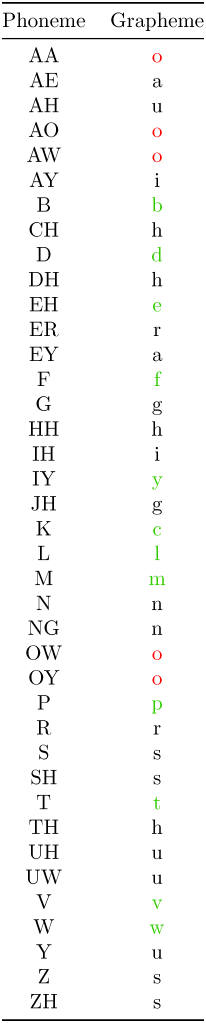

Lets assign now the letters that correlate the highest with the given phoneme. In Python, this would simply be to determine the index with the largest value for each row of the phoneme by using numpy.argmax(M, axis=1). Now for the result!…

Oops! It seems I have reduced the alphabet down to 20 characters… so it is certainly more compact but there are still phonetically ambiguous graphemes present (o, u, g, h, a, i, r, n, s). Anyways, lets see what we get for the tongue-twister we started with:

U ruf-cotud, do-fast, hotful plomun strod hru hu stryts uv scorbro; aftr folin intu u sluf, hy coft und hicupt.

Derp Genratr 2000, Cod Wondrr.

25% less characters; 200% more confusion! It’s not unmanageable but it still requires recognizing specific patterns to the placement of certain characters to recognize what the pronunciation should be… that “the” becomes “hu” is confusing indeed.

A better way?

Clearly, as I did above, just assigning a single character to a phoneme is bound to be non-unique since there are only 26 characters in the alphabet and 39 phonemes so at least 13 phonemes will share some characters. This suggests that we need to look at more than a single character grapheme to correlate the phoneme with. Such a two character pair with a distinct phoneme is called a digraph. In English, the following are such digraphs: ai, ay, ch, ck, ea, ee, ie, kn, oa, oe, oo, ph, sh, ss, th, ue, ui, wh, wr. Using these in our analysis the correlation matrix becomes:

39 phonemes for 45 graphemes.

Alas, as we can see above, most of the digraphs are only weakly correlated with the phonemes, i.e. the single characters have stronger correlation. This may also be due to a relatively lower frequency of digraph usage in the words in general. On the other hand the digraph “th” conveniently filled the gap of high correlation for the phonemes TH and DH that a single letter couldn’t. In any case, now that we have more graphemes than phonemes it is in principle possible to uniquely assign a grapheme to each phoneme. The algorithm is as follows:

- Sort the correlation values from max to min

- Get the row, col index of the highest ranked correlation value,

- The grapheme at the col index assigns it to the phoneme at the row index

- Get the coordinates of the next highest ranked value

- If the row or col index of this value is the same as any previous ones: discard it

- Repeat steps 4 and 5 until all phonemes have been assigned a unique grapheme

In Python, such an algorithm would look like this:

def AssignUniqueGraphemes(M):

M_sorted = np.flip(np.argsort(M, axis=None)) #Flatten the 2D matrix M and get the indices that sort the correlation value from (max to min)

RowCol = np.unravel_index(M_sorted, (np.size(M,0),np.size(M,1))) #Convert to row, col indices

row_list = [] #Create empty list for appending to

col_list = []

for ind in range(len(M_sorted)): #from max to min correlation value...

row = RowCol[0][ind]

col = RowCol[1][ind]

if not row in row_list and not col in col_list: #If neither col or row in the list: append it

row_list.append(row)

col_list.append(col)

if len(row_list) == 39: #If all the phonemes are added: break the loop

break

return row_list, col_list

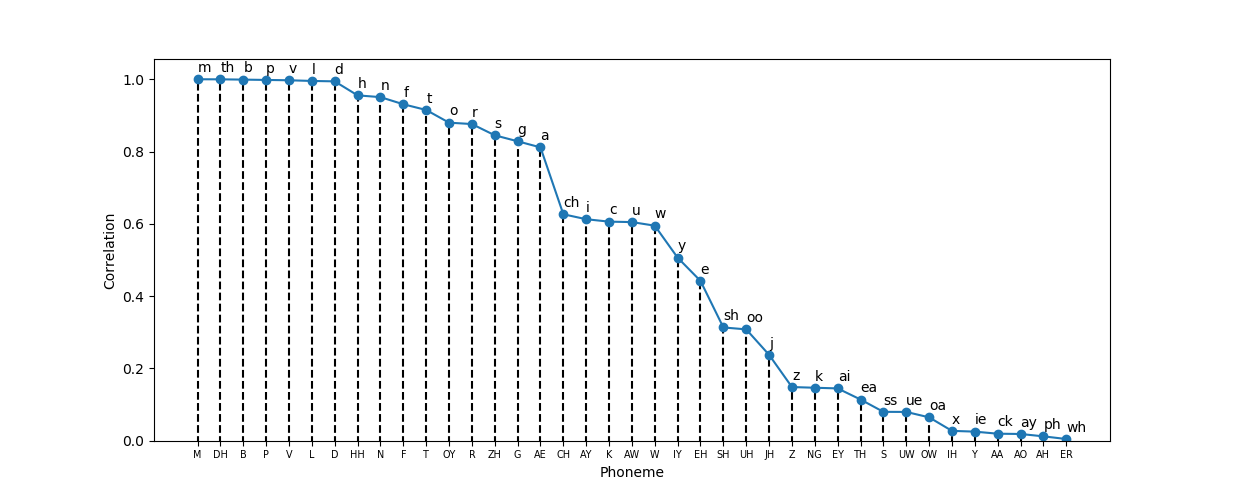

From this algorithm (see my GitHub for the full code) we get:

Seems good! However, as expected, there are some strange assignments, such as AA → ck, ER → wh, and basically all the other ones where there is weak correlation (most of the digraphs). This can be better seen in the following plot:

As we can see above, the grapheme assignment seems reasonable and then it stops making sense after Z → z and we get something strange like NG → k. Note that I may have not included all possible digraphs (some sources indicate other letter combinations) such as “ng”, which would very likely result in the assignment of NG → ng thus resolving this case. Additionally, there are trigraphs (e.g. tch, igh) and even quadgraphs (e.g. ough, eigh. But for extending this list one should be careful whether or not the letter combinations actually produce a distinct phoneme or it is just two separate phonemes (this case is called a blend).

Just for fun lets use the above assignment to see what the tongue twister looks like:

Ph rphf-coatphd, doa-faisst, eaaytfphl plumphn sstroad earue thph sstrytss phv Sscckrbwhoa; aftwh fcklxk xntue ph sslphf, hy cayft phnd hxcphpt.

Derp Jenwhaitwh 2000, Coad Wckndwhwh

…right. The whole AH → ph throws a monkey wrench into the whole thing. Also the ER → wh makes it sound like a Boston accent… at least in my mind. The IH → x makes hxcphtp seem like a name of a Lovecraftian deity (e.g. Cxaxukluth).

What’s next?

The limitation of the above approach of using a correlation matrix is that we have to predetermine what the graphemes could be such as whether or not there are digraphs or multigraphs (more than 2 characters). This could be arbitrarily extended but I want to reduce the usage of multiple character length graphemes as much as possible. Rather than manually trying different combinations: an approach to resolve all the likely graphemes could be similar to deciphering a secret message. But we’ll leave that for next time…!

Also my YouTube channel for AI related projects.